What is owed by rich countries?

The underlying structure of the 2001 Kyoto Protocol was formulated on a simple tenet: developed countries were the ones that upset the dynamic equilibrium of the earth’s carbon cycle with their access and use of fossil fuels to get rich, so why shouldn’t developing countries have that same benefit?

With this in mind, the Clean Development Mechanism carbon offset program was devised (as part of the Kyoto Protocol) to divert financial resources from developed countries to developing countries. One stream was dedicated to funding renewable energy projects where fossil-fuel-generated energy prevailed.

The Clean Development Mechanism also sought to fund projects that would encourage reforestation or afforestation or reward landowners who preserved their forest holdings (rather than remove it in favour of other agricultural pursuits).

Did the Clean Development Mechanism work? I guess it has done a lot of nice things, even significant things, but the scale of finance required has fallen far short of what has been needed.

As part of the Kyoto Protocol, the Adaptation Fund was also created with the mandate to finance concrete adaptation projects in developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse impacts of climate change.

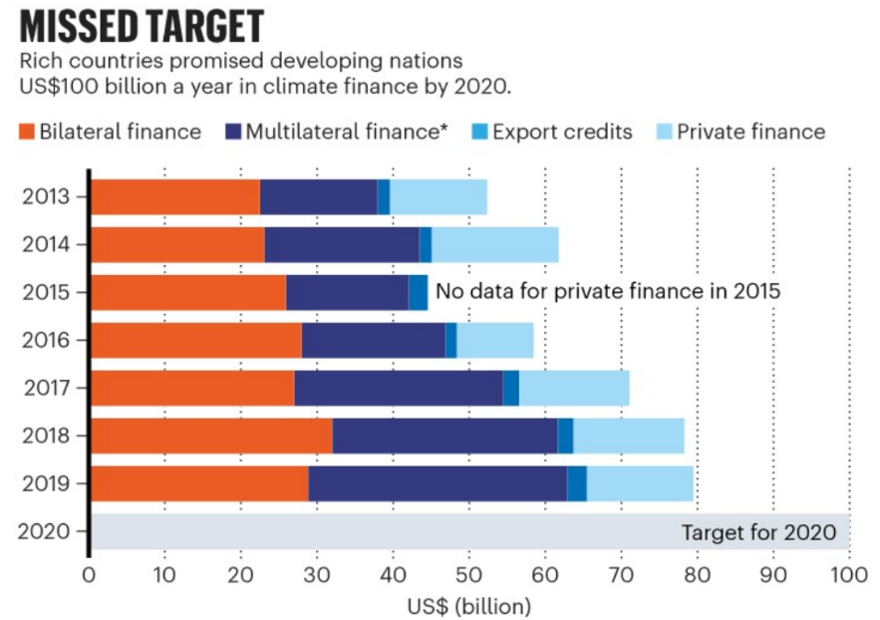

In 2010, twelve years ago, rich nations at the United Nations climate summit in Copenhagen made a significant pledge. They promised to channel US$100 billion a year to less wealthy nations by 2020, to help them adapt to climate change and mitigate further rises in temperature.

It turned out to be a series of missed targets. The graphic illustrates the missed targets (data from 2020 is still being collected). Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-02846-3#ref-CR5

Although rich nations collectively agreed to the $100-billion goal, they made no formal deal on what each should pay. Instead, countries announced pledges in the hope that others would follow.

Multiple analyses of a notional fair share for these payments reach the same conclusion: the United States has fallen far short. The WRI estimates Australia, Canada and Greece also fell far short of what they should have contributed. Japan and France, on the other hand, have transferred more than their fair share — BUT almost all of their funding came in the form of repayable loans, not grants.

In the meantime, other issues within the financing regime rolled on including:

• The imbalance between funds for mitigation as opposed to funds available for adaptation after natural disasters. Donors prefer mitigation projects because success is clear and measurable i.e. solar farms and electric car projects can be quantified by the avoided or captured carbon emissions — whereas it’s less easy to define successful adaptation. Donors also prefer loans, rather than grants which eliminates the likelihood these funds will go to poor people struggling from the impacts of climate change because there is no return on investment.

• Many developing countries are already in significant debt.

• Most of the climate finance is going to middle-income countries, not the poorest, most-vulnerable countries. “Many, many African countries are lamenting that they are not able to jump through the hoops [to access climate finance] because of the complexity and the technicality,” says Chukwumerije Okereke, an economist at Alex-Ekwueme Federal University Ndufu-Alike in Ikwo, Nigeria. “And they’re not receiving sufficient capacity-building exercises and training in this.”

Negotiations for more and better funding arrangements was one of the reasons why the COP26 went into overtime. The G77 + China, which represents 134 developing countries, proposed establishing a funding facility to help vulnerable nations respond to the loss and damages inflicted by an overheating climate.

Despite joining a “high ambition coalition” with small island states and vulnerable nations, the US and the EU have opposed the idea. Loss and damage was one of the most politically contentious issues discussed in the climate talks because it raised the nasty question of historical responsibility for causing the climate crisis. Rich nations have consistently refused to accept liability or calls for compensation.

The UN Environment Program estimates that developing countries need US$70 billion per year for adaptation with this figure expected to double by 2030.

The final outcome of COP26 was that rich countries have so far pledged US$96 billion per annum by 2023, with an agreement that more money be given in the form of grants rather than loans, but the details of that commitment are limited. Of this, a paltry US$356 million comes from new pledges to the Adaptation Fund.

New climate finance pledges include:

• The US has pledged $11.4 billion per year by 2024, as well as $3 billion specifically for climate adaptation (an October report from the WRI – Bos, J. & Thwaites, J. A Breakdown of Developed Countries’ Public Climate Finance Contributions Towards the $100 Billion Goal -World Resources Institute, 2021 – reckoned that the US should contribute 40–47% of the $100 billion, depending on whether the calculation takes into account wealth, past emissions or population. But its average annual contribution from 2016 to 2018 was only around $7.6 billion).

• The UK says it will double its climate finance to $11.6 billion between 2020 and 2025.

• Canada has announced a doubling of its climate finance support to $5.3 billion between 2020 and 2025.

• Japan has offered $10 billion over the next five years for reducing emissions in Asia.

• Norway has committed to tripling its adaptation finance.

• Australia will double its contribution to a whopping US$400 million per year (embarrassing!).

• Spain will increase its climate finance pledge by 50% to $1.55 billion a year from 2025.

We will keep you posted on the progress (or lack of) of rich countries meeting their funding pledges and the mode in which those funds are provided. Certainly, the discussion of what rich countries owe to poorer ones in respect of climate change is not going away any time soon.