A smooth transition to Net Zero requires a strategic plan

In the recently released IPCC report “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability”, one of the conclusions was that “multiple climate hazards will occur simultaneously, and multiple climatic and non-climatic risks will interact, resulting in compounding overall risk and risks cascading across sectors and regions.”

The IPCC doesn’t have to convince me that climatic conditions are going to get worse. As I write from the Blue Mountains in Australia the downpour of rain, like I have never seen before, continues. Forty kilometres away at the bottom of the mountains, record levels of flooding are happening right now. Paradoxically, it was only 2 years ago we faced the horror of widespread bushfires, brought on by an extended drought.

So as climate change impacts become more pervasive, what impact will this have on carbon climate risk in the commercial world?

Obviously, adaptation policy and procedures should be included in climate-related risk assessment. But what of mitigation strategies to help lessen long-term impacts? In particular, a transition to Net Zero status.

Around the world, governments and corporations are feverishly setting Net Zero targets, some short-term, some long-term. This is all well and good, but exactly what are the implications of going Net Zero?

Net Zero has three limbs:

• Calculate the carbon inventory.

• Reduce emissions as much as possible.

• Offset the residual emissions.

A review of corporate reports indicates that the preparation of the carbon inventory is often problematic. The calculation of direct emissions and the indirect emissions of purchased electricity is straight forward, but the inclusion of other indirect emissions, aka scope 3 emissions, is a different matter. this is why using the CarbonView sustainability management platform makes the process so much easier.

Generally speaking, organisational scope 3 emissions represent about 80% of the carbon emissions in a corporation’s value chain. However, it is hard to find a corporation’s sustainability report that shows total scope 3 emissions at any more than the total of scope 1 & 2 emissions.

The rules to determine which scope 3 emissions should be included in a carbon inventory lie with the GHG Value Chain (Scope 3) Accounting & Reporting Standard and ISO Standard 14064.1. In Australia, there are also the rules of Climate Active, the official Australian government carbon neutral program (for program participants only).

To assess which indirect emissions should be included in the carbon inventory, the standards rely on subjective definitions of relevant or significant emissions These definitions are based on general criteria such as “are the emissions large compared to total scope 3 emissions” or “can you influence emissions reduction” of the supplier or customer.

Combined with the numerous subjective criteria are way-out clauses such as “the data is not available”, so the excuse is there to exclude that category of carbon emission from the inventory.

Thankfully, a more quantitative approach to carbon emission inclusion is specified in the GHG Value Chain Protocol at Table 5.4. It includes 8 upstream emissions categories and 7 downstream categories, each with a minimum boundary.

The illustration above is an excerpt from Table 5.4 showing the first two upstream categories. Note the minimum boundary for purchased goods and services: “All upstream (cradle-to-gate) emissions of purchased goods and services”. This category has particular ramifications for wholesalers and retailers.

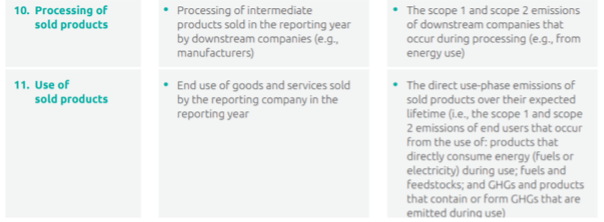

The next illustration shows two of the Table 5.4 downstream categories. Note the Use of sold products category. Let’s say your company sells refrigerators and it sells 1,000 units per year. Let’s say the carbon emissions of those refrigerators, being electricity consumption and refrigerant leakage, are each 500kgCO2-e per year. Let’s assume the refrigerators have a 10-year life. The total carbon emissions each year for those 1,000 refrigerators attributable to the retailer for the next 10 years is therefore 500 tonnes CO2-e per annum.

Of course, for fossil fuel operations, category 11 picks up the emissions of the combustion of fossil fuels sold.

It is noted that the rules for setting targets under the Science Based Targets (SBTi) program specify that at least 67% of scope 3 emissions as per the minimum requirements of Table 5.4 must be included in the target that is set. It is also noted that the SBTi program aligns with the recommendations of the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

So given that the frequency and severity of natural disasters from climate change is going to increase, it is logical to think that the scrutiny of the carbon inventories of corporations will increase too. From a strategic management point-of-view there will be severe implications if the importance of the carbon inventory is discounted amongst ESG responsibility.

The other elephant in the room too, is the projected price for carbon offsets. According to BloombergNEF in their report Long-Term Carbon Offset Outlook 2022, carbon offset prices could climb to over $200 each by 2030.