ESG – a brief history of its development – Part 2

In our previous blog titled “ESG – a brief history of its development – Part 1”, we referred to The Triple Bottomline concept, a framework that balances a company’s social, environmental and economic impacts. Its underlying purpose was to help transform a financial accounting-focused business system to a more comprehensive approach in measuring impact and success. The three-pillar concept includes:

• Environmental preservation measures such as good waste management, abating pollution, reducing GHG gas emissions, preserving biodiversity, protecting forests etc.

• Social equity measures such as enhancing gender parity, fair wages for employees, creating opportunities for disadvantaged groups etc.

• Economic development including the ability of generations to meet their own needs through maintaining a viable economic society today.

ESG has adopted those three pillars of sustainability, with the notable variation to the third pillar. Economic development is replaced with the word governance and hence, the “G” in ESG. The G word refers to governance factors of corporate decision-making from policy-making through to the adequacy of ESG reporting itself.

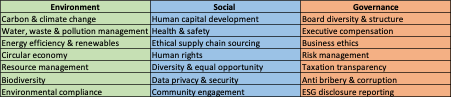

Some of the metrics used for ESG performance are:

ESG development started slowly with players limited to those wanting to do good. In the last 6 years however, the player numbers have increased exponentially as it dawned on investment analysts that ESG methodology is an effective way reduce costs, generate revenue growth and mitigate risk.

Unfortunately, that accelerated interest in ESG has led to an uncoordinated development of the discipline characterised by an alphabet soup of standards, frameworks (globally over 125 of them) and agencies that rate corporate ESG performance (globally over 600 of them) using many and varied metrics for ratings assessment. To add to the confusion, the ESG space is mostly voluntary with different frameworks designed for specific core outcomes.

The good news is that there are movements afoot to consolidate disparate standards and frameworks. Five of the most prominent frameworks and standards are leading the charge. An extract from CDP at https://www.cdp.net/en/articles/media/comprehensive-corporate-reporting reads:

“Transparent measurement and disclosure of sustainability performance is now considered to be a fundamental part of effective business management and essential for preserving trust in business as a force for good. Yet, the complexity surrounding sustainability disclosure has made it difficult to develop the comprehensive solution for corporate reporting that is urgently needed.

In response to this, five framework- and standard-setting institutions of international significance, CDP, the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), have co-published a shared vision of the elements necessary for more comprehensive corporate reporting and a joint statement of intent to drive towards this goal – by working together and by each committing to engage with key actors, including IOSCO and the IFRS, the European Commission, and the World Economic Forum’s International Business Council.

GRI, SASB, CDP and CDSB set the frameworks and standards for sustainability disclosure, including climate-related reporting, along with the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations. The IIRC provides the integrated reporting framework that connects sustainability disclosure to reporting on financial and other capitals. Taken together, these organisations guide the overwhelming majority of sustainability and integrated reporting.”

TCFD is an organization that was established in December 2015 with the goal of developing a set of voluntary climate-related financial risk disclosures that would ideally be adopted by companies to help inform investors and other members of the public about the risks they face related to climate change.

From a regulatory point-of-view, there is movement afoot too. The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) was introduced by the EU in March this year imposing mandatory ESG disclosure obligations on asset managers and other financial markets participants alongside the Taxonomy Regulation and the Low Carbon Benchmarks Regulation as part of a package of legislative measures arising from the European Commission’s Action Plan on Sustainable Finance.

The SFDR aims to bring a level playing field for financial market participants (“FMP”) and financial advisers on transparency in relation to sustainability risks, the consideration of adverse sustainability impacts in their investment processes and the provision of sustainability related information with respect to financial products. The SFDR requires asset managers to provide prescript and standardised disclosures on how ESG factors are integrated at both an entity and product level.

The UK Government confirmed on 29 October that it will make it mandatory for large companies to disclose information in alignment with the recommendations of the TCFD from April 2022. This makes the UK the first G20 country to enshrine the mandate into law, subject to Parliament approval. More than 1,300 of the largest UK-registered companies and financial institutions will have to disclose climate-related financial information on a mandatory basis – in line with the TCFD.

Meanwhile, in New Zealand, beginning in 2023, new laws will require financial firms to explain how they would manage climate-related risks and opportunities with disclosure requirements based on the TCFD standards and the standards of New Zealand’s independent accounting body the External Reporting Board (XRB).